A shortened version of this paper was originally published in Ernest Journal; issue 4, November 2015.

“I do not doubt but the majesty and beauty of the world is latent in any iota of the world; I do not doubt there is far more in trivialities, insects, vulgar persons, slaves, dwarfs, weeds, rejected refuse, than I have supposed…”

—Walt Whitman – Faith Poem

Only in recent studies of the history of photography has the story of our emotional relationship with photography become a subject seen as worthy of discussion in an academic context. Recently, writers such as Elizabeth Edwards, Geoffory Batchen and Joan M. Schwartz have framed discussions of photographic jewelry, mortuary photography, etc through feelings of love and affection in which the indexical relationship to the sitter is embodied by the photograph as a totemic love object.

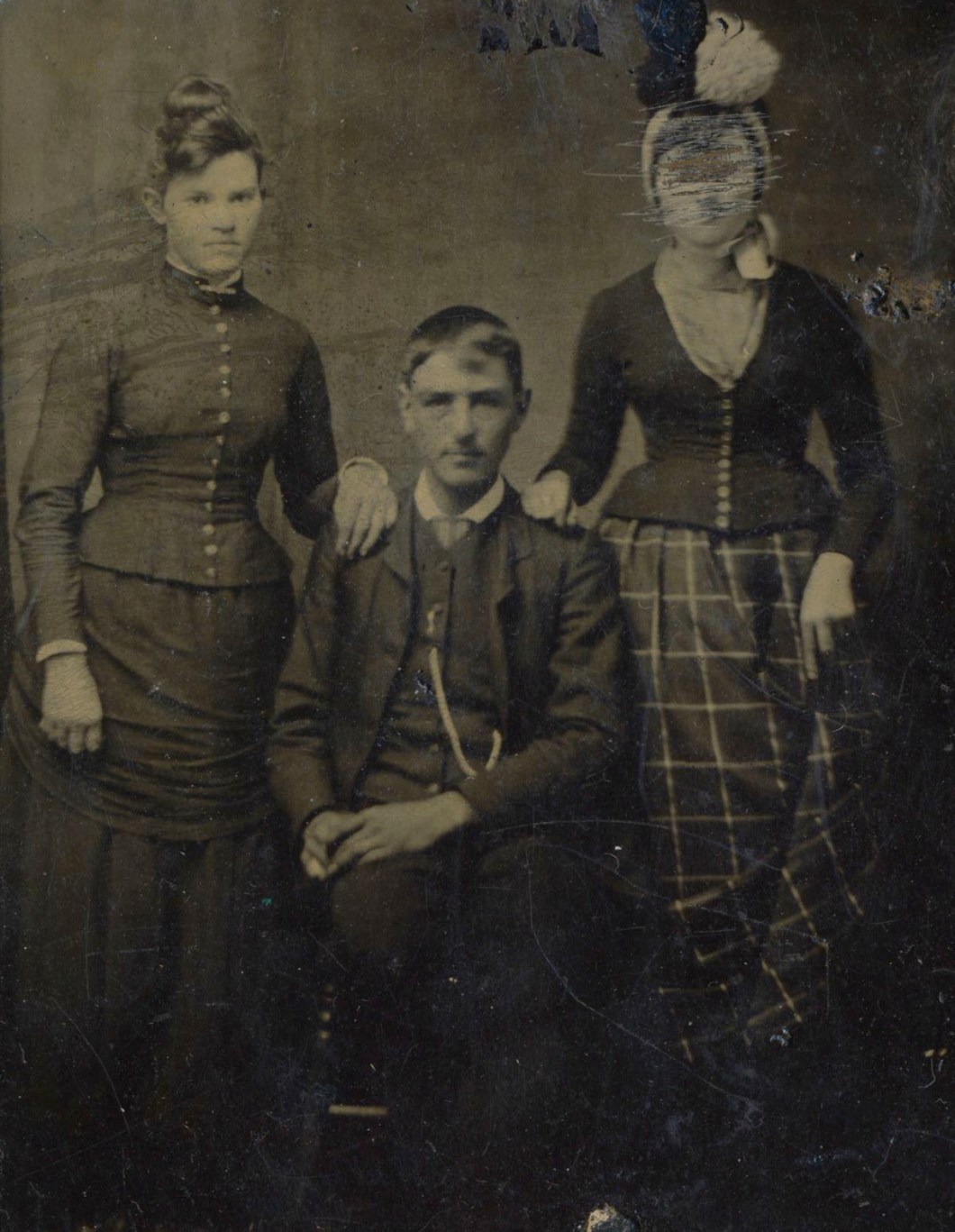

The Tintype was a form of early photography that was extremely popular in the mid nineteenth century, particularly with the working-class of the United States. It was cheap to produce and versatile enough to be sent in the post as the image was printed onto blackened metal. Unlike its predecessor, the Daguerreotype, the cheapness and ubiquity of the Tintype enabled for a lack of consideration of the photographic image as something that should be treasured, held, caressed and loved. As such, it became the first form of photography that could survive having its surface purposefully scratched into and defaced. As an item of cultural expression in the latter half of the 19th Century the Tintype repeatedly bore the physical characteristics of loss and absence through the scratches and marks on its surface as it bore the physical marks of peoples emotional pain in the 19th century.

————-

Almost 40 years before George Eastman issued the first Kodak camera the working and lower class had a form of self-portraiture that was undeniably their own. Walt Whitman’s Great Democratic Vista had finally been realized in the very cheapness and ubiquity of the Tintype, meaning that for the first time, every strata of society could represent themselves, photographically. From ‘occupational tintypes’ of butchers, postmen and anyone exhibiting the tools of their trade, to circus performers and actors, Suffragettes, children, free blacks & Chinese, animals and even the disabled. Those that were regularly disincluded or disenfranchised from the world of which they were part were finally able to prove that they existed.

If you were holding a Tintype in your hands right now, it would be the very plate – the actual object – that sat inside the camera over a hundred and fifty years ago. Its blank, black face might have stared into the face of a young woman, for twenty to thirty seconds, while the lens cap on the camera was removed. She might very well have thought very hard of the person she were to give this portrait to, thus psychically transferring her thoughts, her emotions, onto the plate as the lens transferred a little, miniature vision of herself onto it. The photographer would then have taken it to his darkroom and developed it, whereupon her latent image would be teased out of the darkness to the surface. It would be handed to her, dressed up in gold foil and glass, whereupon she would take it home and write a note inside it, wrap it up in nice paper and string and send it to the man she loved.

This is what photography does. Preserving in Amber the people who are the most dear to us; it offers a reflexive comment on the nature of existing in the world.

The nature of photography is evidence of the trauma of living.

“From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here…a sot of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze”

– Roland Barthe

Photographs are emotional artifacts. They are not passive unyielding pictures. They are social documents that return our gaze and consume our love. Their materiality is central to the strength they have over memory. We need physical photographs that “can be handled, framed… crumpled, caressed, pinned on a wall, put under a pillow, or wept over.”[1]

But what of negative emotions and states such as spite, jealousy and hate in direct relation to photographs? While much has been written about photographs as locums of love and positive emotions, active discourse about negative emotions in photographic studies is rare even today.

Every once in a while in my research as a photographic historian, I encounter examples of Tintypes in particular, upon which the face of the sitter has been disfigured in some way by an unknown hand. Explicit marks are made to the face and, sometimes the hands, such as scratching out or hacking marks. Such specific marks cannot be passed off as merely accidental. Within the flow of history the abuse itself is unseen, it happens ‘Off Camera’. All that remains are the marks of that abuse.

When first I came across instances of this kind of trauma I thought of the cliché of old family snapshots with very specific holes cut around certain heads or strange angles cutting out entire sides of a picture and I felt that they were a very early example of what we have here. I thought of wronged women and men – our own ancestors even – crying as they gouged and hacked at the hard metallic surface of the Tintype and it occurred to me that for the first time in history, and perhaps the last, here was a form of photography that was cheap and ubiquitous enough that, unlike the fancily cased Daguerreotype and Ambrotype, its monetary value was of little import yet it was hardy enough that it had been the favoured photographic form for soldiers during the Civil War so that it could be carried around in the pocket or sent back home intact (there are numerous apocryphal tales of soldiers lives being saved by a bullet in a tintype.)

Due to these factors, a form of ‘psychic trauma’ could be inflicted upon the Tintype wherein it would act as like a totem or voodoo figure for the erstwhile person, taking both the psychical and physical pain of its abuser upon the sitter in the image. Due to its resilient nature, the photograph object could remain largely intact so that either the abuser could be reminded of their hatred for the sitter in their own act of mourning or it could be sent to the sitter as a form of hate mail.

The Abused Tintype becomes a haunted object. Yet, this is the reversal of Freud’s notion of the Uncanny; an object that haunts with all the melancholy horror of an M.R. James story.The Tintype acts as a recipient of that psychic trauma like a totem. The image and the damage imparted upon it become both a receptacle for the suffering of the bearer and also for the psychic damage done to the sitter in the image. The Abused Tintype becomes a reflection of that suffering and a receptacle for it. We are left with nothing but the bare bones of a story. A man, a woman, a violence done. At least a psychic violence – the Abused Tintype becomes the ultimate Vooodoo doll. Instead of a totem to ward off harm, it becomes one that invites it, needs it and begs for the unhappiness that comes with it. The result of trauma suffered and trauma inflicted, like a ghost in the wall, the Abused Tintype wears its violence upon itself, its wails reverberating against its own walls.

Can a photograph be haunted? In a metaphysical sense certainly. The physical marks that these images bear imbue their surface with a sense of unheimlich, that not-at-home-ness of Freud’s creation. The people pictured within them have become doppelgangers for their real selves. Their hollow, ghostly faces, the spirit of those wronged in the past. Here, for the first time, the cheapness and ubiquity of the Tintype enabled for a lack of consideration of the photographic image as something that should be treasured, held, caressed and loved. Instead, Science, art and commerce came together at a point in time that allowed for the photographic image to become the ultimate cursed object of the nineteenth century.

[1] Edwards, Elizabeth,